The National Assembly has been dissolved

After the far right trounced Macron's party in the European elections, the president called snap elections.

It was a European election, but the campaign — and the consequences — were distinctively French.

On June 9, voters in France joined hundreds of millions of Europeans across the continent to make their voice heard in the European Parliament elections. After voting was conducted in overseas departments and territories on Saturday, polling places opened in metropolitan France at 8 a.m. Sunday.

French media are forbidden from relaying results, and candidates from communicating anything other than videos of themselves casting their ballots, before the conclusion of voting. Coverage throughout the day consisted mainly of anecdotes of individual voters interviewed at the polls, along with announcements of overall turnout numbers at noon (19.81%) and 5 p.m. (45.26%), an increase of two percentage points from the last European election in 2019.

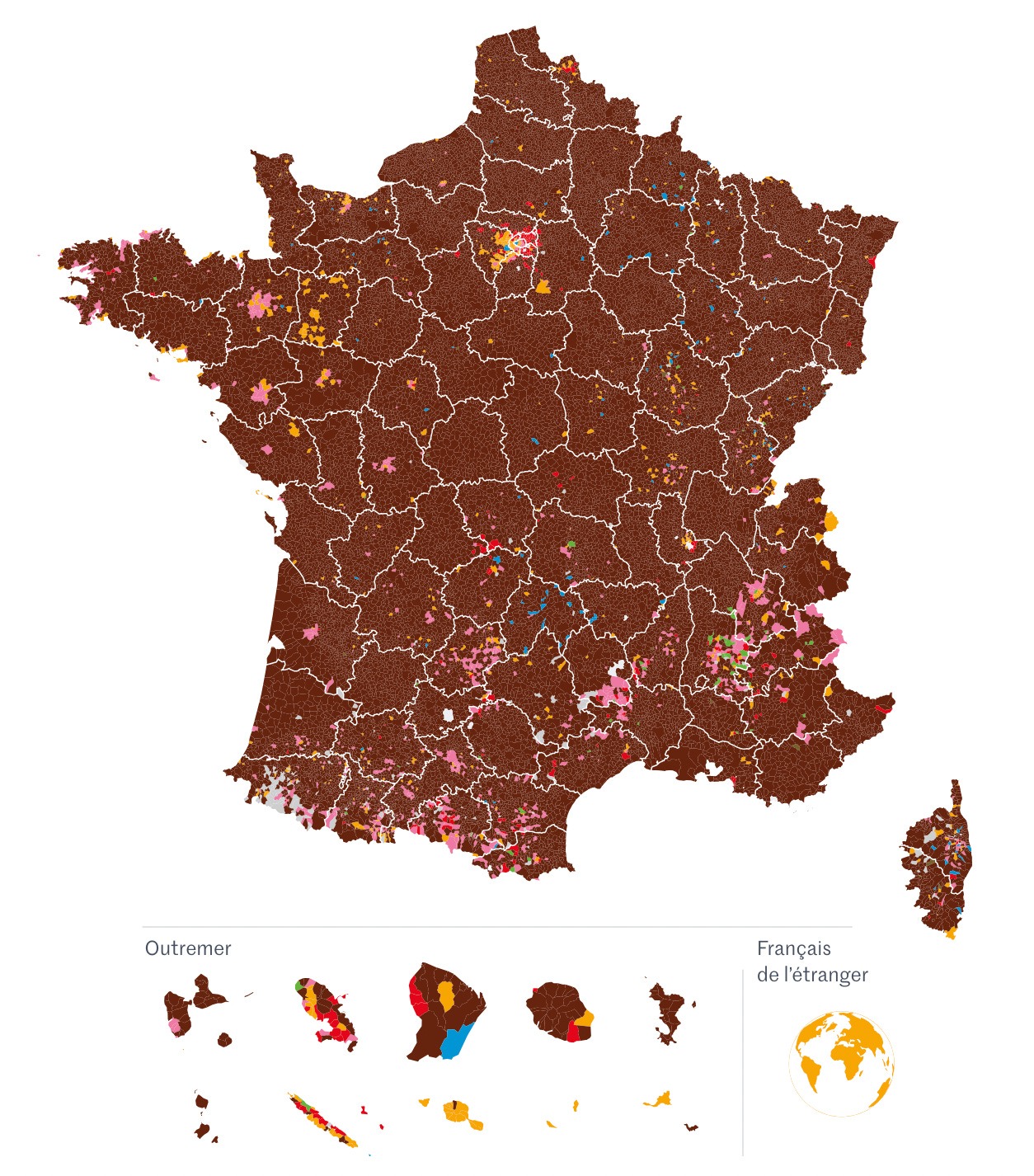

The last polling places in Paris and other large cities closed at 8 p.m., and the news broke quickly: as expected, it was a thumping victory for the Rassemblement National (RN), the far-right party of Marine Le Pen, led by Jordan Bardella, with 31.5% of the vote (according to the latest results as of Sunday night). President Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance party, led by the little-known Valérie Hayer, came in a distant second (14.6%), closely tailed by Raphaël Glucksmann’s Socialist Party/Place Publique (13.8%).

The leftwing La France Insoumise performed more strongly than expected, with 9.8% of the vote. Three other parties cleared the bar of 5% needed to win seats in the European Parliament: the conservative Les Républicains (7.2%), ecologists (5.5%) and Reconquête (5.5%), another far-right list led by Marion Maréchal, Le Pen’s niece.

The results were by no means surprising — they aligned closely with opinion polls throughout the campaign — but they were nonetheless shocking. Even as the RN has steadily gained support over the past two decades, the so-called “republican front” of more moderate parties has until now managed to block its path to power. Now, it will dominate France’s delegation in the European Parliament, and the far right has its sights set on the hôtel de Matignon, seat of power of the prime minister.

Macron: “I’m dissolving the National Assembly tonight”

Within an hour of the announcement of the initial results, the président de la République addressed the French people from the Élysée. After reflecting on the threat posed by the far right for the future of Europe, he revealed just how critical the situation was by ordering the dissolution of the National Assembly:

This is why, after having carried out the consultations provided for in article 12 of our Constitution, I decided to give you the choice of our parliamentary future again by voting. I therefore dissolve the National Assembly this evening. In a few moments I will sign the decree convening the legislative elections which will be held on June 30 for the first round and July 7 for the second.

For those unfamiliar with parliamentary systems, the dissolution of the National Assembly may be a foreign concept. The Constitution of the Fifth Republic empowers the president to do so after consulting with the prime minister and the respective presidents of the National Assembly and the Senate. This act triggers “snap elections” (meaning they are held earlier than planned) within 20 to 40 days to constitute a new Assembly. The Senate, on the other hand, cannot be dissolved.

Across the English Channel, the most famous parliamentary system of all will also hold snap elections in the first week of July. U.K. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak called them for July 4 in a rainy press conference outside 10 Downing Street on May 22.

Macron’s five-minute address at the presidential palace came down on the political landscape like a lightning bolt from Mount Olympus, instantly transforming the conclusion of the European campaign into the starting gun of a four-week legislative campaign that will define the contours of the president’s final three years in office.

Reactions were mixed. Jordan Bardella and Marine Le Pen were jubilant, with the latter emphasizing that the results revealed the RN as “a great force of change” and that “we’re ready to exercise power.” Raphaël Glucksmann accused Macron of “complying with Jordan Bardella’s demands” and of “playing an extremely dangerous game with democracy and institutions,” while expressing optimism about the renewed strength of social democracy. (The socialists more than doubled their score from 2019.) Other leaders of the left, including François Ruffin (La France Insoumise), Olivier Faure (socialists) and Marie Toussaint (ecologists) called for an alliance of parties on the left to counter the presumed strength of the far right.

Von der Leyen: “The center is holding”

Amid the brouhaha in the Hexagone, it’s easy to lose sight of the stakes of this election for the future of the European Union. In addition to France, the far right made gains in countries like Germany, Austria and the Netherlands. The Fratelli d’Italia party of Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s ultraconservative prime minister, came in first ahead of the center-left Democratic Party — “cement[ing] her role as a key Brussels power broker,” according to Euronews. The Greens and centrist Renew parties were each set to lose about 20 members of the European Parliament, which mirrors the decline of the ecologists and Renaissance in France.

Even with the rise of the far right, there may not be a dramatic shift in the balance of power in Strasbourg. The center-right European People’s Party (EPP) maintained its position as the largest party in the Parliament and was projected to gain 11 seats as of Sunday night. This is welcome news for European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen (a member of Germany’s conservative CDU party and the lead candidate for the EPP), who is seeking a second term and who needs the Parliament’s approval to remain in office.

Von der Leyen and Meloni have proven to be close allies since the latter came to power in 2022, with Meloni working to reshape Europe in line with her rightwing values. With the Parliament tilting to the right, it will be interesting to observe how the von der Leyen–Meloni alliance develops. For now, von der Leyen is striking a moderate tone, offering to work with the socialists and liberals (which means centrists in the European context) to build a coalition:

"In other words, the center is holding," she said. "But it is also true that the extremes on the left and the right have gained support and this is why the result comes with great responsibility for parties in the center."

What’s next in France

So begins a mad dash to the first round of France’s snap legislative elections on June 30. According to Libération’s analysis, Macron hopes that by acting boldly to dissolve the National Assembly, he can dent the RN’s momentum and recalibrate Renaissance’s electoral fate. But given the strength of Marine Le Pen’s party and the withering of Renaissance’s base, it’s very possible that the far right will emerge as the Assembly’s largest party and gain access to Matignon for the first time. This would result in a “cohabitation,” with a president and prime minister from opposing parties, for the first time since 2002. (More on the implications of cohabitation here.)

Another important unknown in the upcoming campaign is how the left will fare. As I have discussed previously, the Israel-Gaza conflict has fractured the “Nupes” coalition of the socialists, ecologists, communists and La France Insoumise. Will the parties be able to put aside their differences to mount a united front as a credible alternative to the RN and Renaissance?

Although the dissolution of the National Assembly is arguably the most dramatic twist in Macron’s presidency, it’s just the latest sign of the diminishing power of Macronism. Since failing to win an absolute majority in the 2022 legislative elections, the president’s second term has been defined by legislation pushed through the Assembly without a vote (as in the case of the pension reform) or through politically unfavorable deals (as in the case of the immigration law), mass mobilization in protest, and a series of government reshuffles to regain momentum.

If Macron’s calling snap elections represents a big gamble, it shows that the hole he had dug for himself and his party in the run-up to Sunday’s vote was even bigger. And with that, back to the campaign trail we go.

Thanks for reading! If you have any questions about the results of the European elections and what’s next in France, let me know in the comments. And if you need a refresher on how the elections work, including how seats in Strasbourg are awarded, check out my post from April.

European elections 101

April is here, which means the European elections are less than two months away! Voting doesn’t happen as often in France as in the United States: unlike the House of Representatives, whic…

I'm agog, both at the far right success and at the dissolution. The latter may turn out to be either a disaster or a stroke of genius for Macron and his party. Observing with interest from the other side of the Atlantic!