On January 11, two days after Gabriel Attal became the youngest prime minister in French history, Alexis Kohler, the secretary-general of the Élysée, stood behind a white lectern bearing the insignia of the French presidency and read a list of names. Kohler’s delivery was slow and methodical, and he seemed mildly uncomfortable (though not nervous) squinting into the glare of the camera. He is, after all, a civil servant, not a politician — but he holds one of the most influential positions in the Republic as President Emmanuel Macron’s right-hand man.

Together with Attal, the 14 ministers whom Kohler announced constitute the new French government, charged with advancing Macron’s agenda for the country. Several of the ministers are the poids lourds (heavyweights) of the previous government led by former Prime Minister Élisabeth Borne: Bruno Le Maire, economy and finance minister; Gérald Darmanin, interior minister; Éric Dupond-Moretti, justice minister; and Sébastien Lecornu, armed forces minister. Along with the minister for Europe and foreign affairs (now Stéphane Séjourné, who replaced Catherine Colonna), these men lead the ministères régaliens (literally, sovereign ministries), which oversee the core functions of the state and hold the most power.

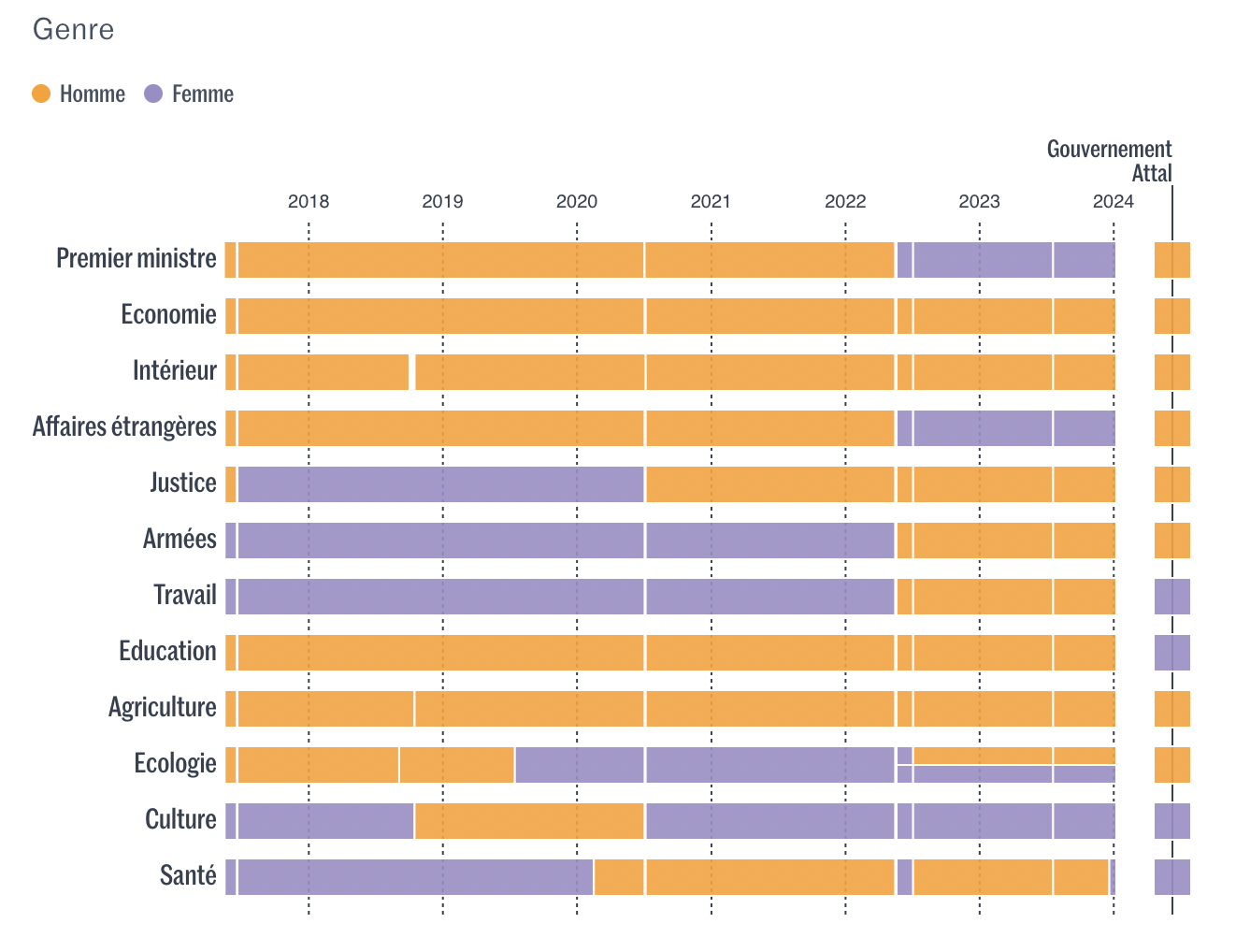

Though this government technically adheres to a policy of gender parity (eight men, seven women), the press was quick to note that women were excluded from all of the top posts, and three of them are actually ministres déléguées (deputy ministers) who serve under the prime minister. Even during Borne’s premiership, the High Council for Equality between Women and Men lamented that parity was “hollow” and didn’t correspond to real power-sharing between the genders.

Despite their relegation to the less powerful ministries, the women who have been newly named to the government have received the lion’s share of media attention. One in particular — Culture Minister Rachida Dati — generated an extraordinary amount of buzz by agreeing to work under Macron, shifting the equilibrium of both national and Parisian politics and diverting attention from the record-breaking prime minister and even the Jupiterian président de la République whose gravity defines his ministers’ orbits.

Rachida Dati, or the return of Sarkozysm

If you’ve been following French politics for the past two decades, Rachida Dati is a familiar name. The daughter of Moroccan and Algerian immigrants from a modest background — an identity she proudly claims — she has come to inhabit the highest echelons of French conservatism. After serving as former President Nicolas Sarkozy’s justice minister from 2007 to 2009, she spent a decade as a member of the European Parliament (MEP), and has served as mayor of Paris’s 7th arrondissement for over 15 years. (The 7th arrondissement is home to 10 of the 20 richest neighborhoods in the capital, along with many government ministries, including Matignon.) Dati is the leader of the opposition to Mayor Anne Hidalgo in the Council of Paris, and came in second in the 2020 mayoral race with 34% of the vote in the runoff. Dati’s enduring political success is all the more remarkable given the legal problems she faces: she’s currently mise en examen (under investigation) for “passive corruption and concealment of abuse of power” related to legal consulting fees she received from Renault-Nissan while serving as MEP. Macron and Attal have emphasized the importance of respecting the presumption of innocence to justify her appointment.

When Alexis Kohler read “Rachida Dati, ministre de la culture” from behind the lectern at the Élysée, it launched a shockwave through the political landscape, for several reasons. First, Dati has no particular expertise or interest in cultural affairs. (The culture minister whom she replaced, Rima Abdul Malak, on the other hand, was formerly cultural attachée in New York and Macron’s cultural advisor.) Second, by her own admission, Dati’s singular focus in recent years has been to capture the mayoralty of Paris. In fact, she announced her candidacy in the mayor’s race on Wednesday, less than a week after her appointment to the government. Third, she had no prior political alliance with Macron — and repeatedly expressed skepticism of, and even hostility toward, his centrist political project. (She has, however, reportedly been close with Brigitte Macron for a decade.)

But the most significant reason Dati’s inclusion in the new government stunned the media is that her politics hark back to a former era. Since Sarkozy lost his reelection bid to François Hollande in 2012, Dati has remained one of the most prominent former members of his government, and she continues to incarnate his particular brand of conservativism — Sarkozysm. Commentators have noted the echoes of Sarkozy in Macron’s and Attal’s new priorities, and even the language and style they use, with some going so far as to call the rebranding effort “a copy-paste of the Sarkozy method”:

For each priority — safety, school, health, etc. — a field trip intended to demonstrate listening and empathy. The facial expression is always serious, the words used are simple, going against the technocratic vocabulary used by the government of experts once favored by the President of the Republic.

— Françoise Fressoz, Le Monde

Despite all of the upheaval in French politics in the past 12 years — the birth of Macron’s centrist party Renaissance, the collapse of the traditional left and right parties (at least in presidential elections), and the creeping rise of the far right — Dati’s return to the government signals a potential return to a more conventional conception and practice of politics, including a focus on the middle class and emphasis on “common sense.” The appointment of Catherine Vautrin, who served in former President Jacques Chirac’s government from 2004 to 2007, as the new minister of labor, health and solidarity, adds another data point to this analysis.

Given Dati’s heavy involvement in local Parisian politics, her ministerial appointment has also irreversibly altered the landscape of the 2026 municipal elections. Le Monde reported that she accepted to join Macron’s government only after making a deal with the president that he would back her to lead a coalition of his Renaissance party and her Les Républicains (LR) party in the local race. This would be a major setback both for Renaissance hopefuls for the mayoralty, including former Transport Minister Clément Beaune, and for LR, who see the deal as a threat and have launched proceedings to remove Dati from the party.

While the municipal elections are over two years away — an eternity in politics — the deal also poses a major threat to Hidalgo (if she runs again) or to her chosen successor (if she doesn’t). The socialist easily won reelection in 2020 only because the opposition was split between Dati and former Health Minister Agnès Buzyn, who won 13% of the runoff vote while representing Macron’s party. Dati’s new role is sure to add color to her already explosive rivalry with Hidalgo, particularly because important decisions related to the capital, including the redesign of the Place de la Concorde and the reopening of Notre-Dame, are expected to cross her desk. Upon learning of Dati’s appointment, Hidalgo posted a message on her WhatsApp and Instagram accounts wishing “good luck” to cultural actors “given the trials they will go through” while working with the new minister. When it comes to Hidalgo and Dati, it’s personal.

Old methods, new momentum?

In a rare press conference on Tuesday, Macron called on his government to work with “boldness, efficiency, action.” While the naming of Attal and a new slate of ministers was intended to give his second term “new momentum,” the return of conservative figures like Dati and Vautrin is strong evidence that Macron is leaning into the rightward tilt of his government in the hope of winning over voters tempted by LR and Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National in the European Parliament elections in June. But by all but abandoning the left wing of his party, and by adopting many of the strategies that took Sarkozy to the Élysée in 2007, he puts the very meaning of Macronism — which began in 2017 as a singular centrist movement meant to surpass the left-right cleavage that has traditionally defined the politics of the Fifth Republic — at risk.

Thanks for reading! What do you think the consequences of Dati’s appointment to the government will be? What questions do you have? Let me know in the comments!

What a week in France! An artful and insightful political commentary - told with a touch of drama, linguistic precision and lyrical notes... as in "the Jupiterian président de la République whose gravity defines his ministers’ orbits."

My goodness, so much in the way of shenanigans!!! No wonder I hate politics! I really liked your insights that in politics two years is an eternity and that between Hidalgo and Dati “it’s personal.” As always, really appreciate your wise analyses!